Europe is ageing and the health workforce crisis puts the quality and availability of healthcare at risk, especially in elderly care. Artificial Intelligence (AI) solutions may alleviate the health workforce crisis and contribute to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health for all in an ageing Europe. At the same time, however, these solutions may create new-and unforeseen-human rights challenges. Given the fragmented regulatory framework governing medical AI and the lack of sector-specific standards and implementation guidelines, it is difficult for healthcare institutions, health professionals, and informal caretakers to determine how AI can be deployed in elderly care in a manner that respects, protects, and realises the human rights of older patients. In this light, this chapter introduces the outlines of a patients’ rights impact assessment (PRIA) tool for AI in healthcare. The proposed model is sector-specific and takes the form of a self-assessment questionnaire to inform decision-making.

Please cite as: Hannah van Kolfschooten, ‘A Human Rights-Based Approach to Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Proposal for a Patients’ Rights Impact Assessment Tool’, in: Philip Czech, Lisa Heschl, Karin Lukas, Manfred Nowak, and Gerd Oberleitner (eds.), European Yearbook on Human Rights 2024. Brill Publishing, 2024, forthcoming. Link to pdf

1. INTRODUCTION

Europe is ageing. In 2022, more than one-fifth (21.1%) of the European Union (EU) population was aged 65 and over.[1] The need for healthcare is rapidly increasing due to the changing demographics, and at the same time, the health and care workforce is declining. The growing trend of ‘double ageing’ puts further pressure on the – already fragile – healthcare systems in the EU.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) warns that, if not significantly changing direction, the ‘health workforce crisis’ puts the quality and availability of healthcare at risk.[3] In particular, the future of elderly care is volatile. All throughout Europe, governments struggle to find the health personnel to ensure access to essential healthcare for older patients.[4] For example, in the Netherlands, nursing homes had a workforce shortage of 17,900 people in 2021, while the required capacity of nursing homes is expected to almost double by 2040.[5]

Diminishing accessibility of high-quality healthcare is not only an issue of public health – it is also a human rights issue. The health workforce crisis has serious repercussions for the realisation of the right to health, as protected under various instruments of international and EU human rights law.[6] In light of the right to health, States must make every possible effort to guarantee health services, goods, and facilities that are available, accessible, acceptable, and of good quality – without discrimination.[7]

Driven by the Covid-19 pandemic, technological responses to capacity issues in healthcare are gaining more popularity.[8] European governments are also advocating for more use of ‘labour-saving technologies’ in healthcare. Technology using Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often mentioned as the key solution to the health workforce crisis.[9] AI technology can simulate a certain degree of human intelligence, thereby taking over human tasks and solving complex problems. AI makes use of large amounts of data to predict a particular outcome, such as medical diagnoses, disease progression, or the best treatment method, or analyse a specific situation, such as vital signs or sleep patterns.[10] In elderly care in Europe, AI technology is already widely used. Examples include tools for monitoring and surveillance of activity, robotics for non-medical assistance and services,[11] and all kinds of smart health technologies, such as smart incontinence materials and smart beds.[12] The underlying idea is that such tools improve the quality of care, reduce workloads, and cut healthcare costs.[13]

However, the risks medical AI poses to patients are often overlooked. First, the use of AI can directly affect the health status of older people: AI often does not work as well for older users. Research shows frequent ‘biases’ towards age in the datasets used to develop AI technology.[14]Second, the use of AI in elderly care also threaten the protection of the human rights of patients, especially regarding the rights to non-discrimination, protection of personal data, informed consent, and respect for physical and mental integrity.[15] These risks arise from the large scale at which AI systems collect and share sensitive personal data, the risks of bias and discrimination, and the specific vulnerabilities of people in need of care. The impact is even greater for older persons[16] – who are already more vulnerable to human rights violations.[17] For example, systems used in elderly care may contain cultural and racial biases. They can also significantly influence older people’s behaviour, and thus freedom and autonomy.[18] In turn, violations of these rights can also impact the right to health. The WHO specifically warns against age discrimination caused by AI in healthcare.[19]

This creates a complex conundrum. AI solutions may indeed alleviate the health workforce crisis and contribute to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health for all in an ageing Europe. At the same time, however, these solutions may create new – and unforeseen – human rights challenges. For healthcare institutions and health professionals, it is difficult to determine how AI can be deployed in line with human rights obligations. Currently, the regulatory framework governing medical AI technology in EU member states is highly fragmented. It is scattered across different institutions on the European continent, from the WHO to the European Commission, to the Council of Europe, to national governments.[20] Recently adopted AI regulations in Europe (e.g. the EU AI Act and the Council of Europe’s AI Convention) are horizontal and do not specifically regulate the healthcare sector. The development of standards and implementation guidelines for AI in healthcare as part of the EU AI Act is a lengthy process. Human rights, however, apply universally across EU member states[21] and are an important source for patients’ rights protection.[22]

Against this background, the central question of this chapter is as follows: Considering the increasing use of AI technology in healthcare – and especially elderly care – how can AI technology be deployed in a manner that respects, protects, and realises human rights? To answer this question, it is important to (1) identify the potential risks of AI for health and human rights, and (2) assess the extent to which potential risks can be eliminated or mitigated. The ultimate objective is to introduce the outlines of a patients’ rights impact assessment tool for AI in healthcare. Healthcare institutions and health professionals can use this instrument to determine whether a specific medical AI tool respects the patient’s human rights in a specific healthcare setting. This chapter uses AI in elderly care as a case study to illustrate the application of the patients’ rights impact assessment tool for AI.

The chapter is structured as follows. Section 2 examines the use of AI in elderly care as a solution to the healthcare workforce crisis. Section 3 describes the normative framework, placing the protection of patients against the harms of medical AI in the context of the human rights-based approach to health. Section 4 describes the contours of the right to health and offers insights into the challenges of the increasing use of AI for the protection of patients’ rights. Section 5 first provides a legal gap analysis to ascertain how the current regulatory system protects human rights in relation to medical AI. This section proposes the outline of a patient rights’ impact assessment tool for AI in healthcare. Section 6 concludes.

2. SETTING THE SCENE: AI TO COMBAT SHORTAGES IN (ELDERY) HEALTHCARE

Deploying technological solutions in elderly care is not a new development. ‘Gerontechnology’ has been used in home care and nursing home care since the late 20th century, primarily aimed at enhancing the autonomy and self-determination of older patients. In addition, technology is also increasingly used to support caregivers and save labour.[23] Monitoring technology such as portable alarm buttons and fall detectors, motion sensors in bed, and GPS trackers have been used in elderly care for decades.[24] Smart home technology is also well-integrated nowadays, such as automatic lights and doors.[25] In nursing homes, remote care or ‘telehealth’ has been prevalent for some time, such as video consultations. The ethical implications of such ‘smart home’ technologies in elderly care, including concerns related to autonomy, human dignity, and privacy, have been extensively discussed.[26] Legal research has particularly focused on issues surrounding the protection of personal data and liability in the event of accidents.[27]

The integration of AI in technology for elderly care brings about new challenges for the ensuring of high-quality care and the safeguarding of patients’ rights. Unlike traditional sensor technologies, which operate on straightforward conditional logic (e.g., issuing an alarm notification to the caregiver if the bed sensor reports an unoccupied bed for more than 10 minutes between 23:00 and 07:00), AI-powered sensors possess the capability to autonomously determine the necessity and nature of interventions in specific situations. AI systems analyze vast amounts of data, including personal information from multiple sources, to identify patterns in an individual’s daily activities. This analysis enables the detection of deviations from established patterns, upon which the AI algorithm can autonomously decide on the most appropriate course of action. This nuanced technological approach, while potentially offering more personalised and efficient care, raises significant concerns regarding privacy, autonomy, and the broader implications for patient rights in the context of elderly care.

Nonetheless, because of its potential to reduce workload, AI is increasingly considered in elderly care. Generally, AI technology tools for elderly care can be divided into three categories: (1) Home automation, monitoring and sensors, (2) Care robots, and (3) Medical decision support. Technology in categories 1 and 2 is mainly deployed in older people’s homes and nursing homes, while technology in category 3 is primarily used in a clinical environment (e.g. at the GP or in the hospital). This section provides a rough overview of existing AI tools and outlines their benefits and risks. Nota bene, AI is not yet the standard in elderly care, but its development is skyrocketing.

2.1 HOME AUTOMATION, MONITORING AND SENSORS

AI domotics (or AI home automation) can offer many benefits in elderly care. AI domotics can adapt to users’ needs and preferences. A key example in elderly care is the voice assistant with voice recognition to assist with medication tracking, scheduling medical appointments, and providing health advice. AI domotics such as smart mattresses, cookers, and lights are increasingly being used.[28] AI also plays a growing role in monitoring older patients, such as wandering detection systems with face recognition, and cameras with emotion recognition for the detection of mental health issues.[29] In addition, AI systems are used for fall detection. Wearables (e.g. watches) and sensors are also used to measure and analyse important health data (e.g. heart rate, blood pressure, and movement patterns) and share information with health professionals or family members. In addition, smart sensors can track food and liquid intake. Another example is AI incontinence material, where a sensor measures and predicts when it needs changing.[30]

AI care robots can perform various functions in elderly care, from medical support, assistance in daily activities and housekeeping, to social functions. Some types of robots communicate directly with patients, while others are mainly designed to support caregivers in their activities, such as the lifting of patients.[31] Social robots can talk and move and are capable of automatically adapting to the living patterns of the specific person. They are regularly used to entertain lonely patients, for example in the form of robot pets for companionship. Another example is the use of anthropomorphic robots that are used to vocally remind patients to take their medication.[32] Care robots are increasingly integrated with AI sensors and cameras, allowing them to also fulfil a preventive function by, for example, contacting a caregiver in case of divergent behaviour of the older patient.[33]

Approximately half of healthcare costs in European countries are incurred by people over the age of 65.[34] Their healthcare journey usually starts with a visit to the general practitioner (GP) or family doctor. In this first stage of healthcare, AI is increasingly used by health professionals. For example, in the Netherlands, GPs have access to ‘NHGDoc’, a medical decision-support system integrated into many information systems used in GP practices. The system uses AI technology to compare the information in a specific medical record with general medical guidelines. On this basis, it suggests a diagnosis and treatment recommendations. The same system contains a personalised side-effect finder.[35] AI is also increasingly being used in specialist medical care. For instance, AI systems are used in diagnostics, for example, to analyse medical images such as X-rays, MRI scans, and CT scans to detect early signs of cancer.[36] AI can also assist in creating treatment plans tailored to the individual needs of older patients and predict survival rates and prognoses for cancer patients based on clinical data and medical history.[37]

What these AI systems have in common is that they collect a lot of personal information about the individual patient, including a lot of information about health status. This information is used to build a detailed profile of an older person’s lifestyle and health, based on which systems are automatically adapted to individual needs or can make predictions about future behaviour. In addition, health information is often automatically shared with informal caregivers or health professionals, often via mobile apps. Commonly cited benefits include increasing independence and autonomy for older patients, fewer accidents, cost savings, and labour savings. At the same time, the increasing use of AI applications in elderly care creates tension with the protection of various human rights. The next section discusses the importance of a human rights-based approach to health.

3. TAKING A HUMAN RIGHTS-BASED APPROACH TO HEALTH

The intrinsic link between health and human rights is the focus of the ‘health and human rights’ scholarship, which can be seen as a specific branch of human rights law.[38] There are three important interconnections between health and human rights. First, human rights violations also affect the health and well-being of both individuals and population groups, for example in the case of abusive treatment of prisoners.[39] Second, the manner in which health policies and programs are shaped, can either promote or violate human rights, for example when the government demands quarantine from citizens infected with Covid-19.[40] Finally, the effective enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is dependent on the promotion and protection of other human rights. While all human rights are important for the protection of human health, civil rights such as the right to life and the right to private life, and social rights such as the right to health and the right to food are more often invoked in this context.[41]

3.1 THE HUMAN RIGHT TO HEALTH

Indeed, the key principle within the health and human rights scholarship is the understanding that health is a fundamental human right in itself. The legal basis for the right to health as a human right is the WHO’s recognition of ‘the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health’ as a human right. The legal obligation of states to respect, promote, and fulfil the right to health for all individuals is embedded in various human rights instruments.[42] As explained by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in its General Comment on the right to health, the right to health extends to both high-quality healthcare and to the underlying determinants of health. A key element of the right to health is secure the availability (of health services and resources), the accessibility (physically, financially, and without discrimination), acceptability (from a cultural, ethical, and medical perspective), and quality of healthcare.[43] In relation to the underlying determinants of health, the right to health protects a range of conditions that are necessary to protect health, such as clean drinking water. [44] In this light, the right to health creates responsibilities for States in various areas to shape the conditions necessary for health and to ensure access to adequate healthcare. States must adhere to the principle of progressive realisation and take appropriate measures towards the full realisation of the right to health to the maximum of their available resources.

To operationalise human rights to improve health outcomes and equity, it is essential to take a human rights-based approach to health.[45] The human rights-based approach to health is a normative framework that applies national, regional, and international instruments of human rights law to a wide range of health-related issues,[46] such as mental health,[47] communicable diseases,[48] medical technology,[49] and reproductive health.[50] The underlying idea is that ‘health and human rights are both powerful, modern approaches to defining and advancing human well-being’.[51] Advocates for the human rights-based approach emphasise the legal obligations of states in parallel to the empowerment of individuals and communities to claim their health rights. In the context of EU member states, the human rights-based approach to health has gained increasing recognition and has been integrated into various health policies and practices. Article 35 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFREU) specifically introduces the right to healthcare as part of the EU human rights framework. This chapter focuses on a subset of health-related human rights: the rights of patients.

3.2 PATIENTS’ RIGHTS AS HUMAN RIGHTS

Patients’ rights are a subset of human rights specific to the context of healthcare centred around the patient-health professional relationship.[52] The formulation of specific human rights for patients is warranted by the sensitive nature of the patient-health professional relationship. The patient-health professional relationship is inherently unequal because of the intimate and critical context of healthcare, the patient’s position of vulnerability and dependency when in need of healthcare, and the asymmetric power and knowledge levels between patient and health professional.[53] The protection of the rights of patients can be seen as a legal means to safeguard individuals in this vulnerable position. Equipping patients with individual rights can protect them against the undesirable actions of health professionals and balance out the relationship. Therefore, patients’ rights are primarily addressed to health professionals and are often formulated as legal obligations and connected rights. Taking a human rights-based approach, the rights of patients are not viewed in isolation but are integrated into the broader context of universal human rights. However, because patients’ rights are rooted in more than human rights law, they cannot be considered a regular branch of human rights law.[54]

Patients’ rights in EU member states are protected in a multi-layered system. Most importantly, patients’ rights are protected nationally at the level of the EU member states, either codified in laws, as non-binding instruments in professional guidelines or codes of conduct, or in combination. Almost all EU member states have a special national law for patients’ rights protection in place.[55] Another layer is formed by the human rights laws applicable in the EU member states. The CFREU and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) are the most important legal sources in which patients’ rights can be found.[56] Another legal source is the Council of Europe’s European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine.[57] Rights of specific patient groups are also protected in specific human rights instrument such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Older people also enjoy a special position of protection, for example in Article 25 CFREU: ‘The Union recognises and respects the rights of the elderly to lead a life of dignity and independence and to participate in social and cultural life.’

Both the European Court of Justice (CJEU) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) increasingly apply human rights to the context of healthcare and interpret general human rights to also include specific patients’ rights,[58] for example by reading a ‘right to be informed when consenting to medical interventions’ into Article 8 ECHR.[59] This way, patients’ rights acknowledged in the context of human rights enter the national legal order either directly via states’ legal obligations or via domestic legal proceedings initiated by individuals.

As a result of this wide range of legal sources underpinning patients’ rights, a generally accepted exhaustive list of patients’ rights does not exist. This also means that the exact interpretation and application of these rights differ from Member State to Member State.[60] However, because of their recognition in the European human rights framework and their shared roots in the notion of human dignity, a set of ‘core patients’ rights’ can be identified as (1) the right to access to healthcare; (2) the right to autonomy; (3) the right to information; (4) the right to privacy and confidentiality; and (5) the right to effective remedy.[61] The next Section explains how the rights of older patients are potentially threatened by the increasing use of AI systems in healthcare.

4. CHALLENGES TO PATIENTS’ RIGHTS OF OLDER PATIENTS

Older patients are more at risk of human rights violations. Generally, old age renders people more susceptible to illness, pain, and death. From this perspective, older people are in more need of support and healthcare, which makes them more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. There is ample evidence of growing age discrimination and stereotyping of older people. This also extends to the area of healthcare: the protection of older people’s right to healthcare is under pressure, according to a recent WHO report on global age discrimination.[62] Older patients are often not taken seriously or given the pain medication they need. Older patients may also face barriers to accessing healthcare services due to physical limitations, lack of transportation, and financial constraints.[63] Patients living in care homes are frequently deprived of their liberty, for example due to locked doors, intensive telemonitoring, or coerced use of medication. Moreover, they are often unable to consent to their placement and specific treatment because of mental capacity issues.[64] Besides reported instances of violence against older patients in nursing homes or long term-care facilities are increasing.[65]

Indeed, the health workforce crisis puts the availability of healthcare at risk, especially for older patients.[66] In principle, everyone has equal access to healthcare. Yet, what happens to the right to health if there are not enough resources to meet everyone’s demand for care? During the Covid-19 pandemic, there was much debate about how to allocate ICU treatments for critically ill patients in a situation of scarce resources.[67]Old age was often mentioned as a criterion that should be considered in allocating resources.[68] Now, States are considering the deployment of AI technology in elderly care to ensure continued access to essential healthcare. This could be seen as a reallocation of the scarce resource of health personnel. Ultimately, the decision on prioritisation is a political one, that must, however, be taken in accordance with human rights and principles.

Against this background, the WHO is concerned about the impact of the increasing use of AI in healthcare settings on older patients.[69] The following paragraphs discuss the challenges AI creates for the protection of patients’ rights of older patients, specifically concerning the right to access to healthcare; the right to autonomy; the right to information; and the right to privacy and confidentiality.

4.1 ACCESSIBLE, AVAILABLE, AND ACCEPTABLE HEALTHCARE

Everyone has the right to access to healthcare. This means that healthcare needs to be accessible, available, and acceptable. The increasing use of AI in elderly care may create barriers to this right. Take the case of digital literacy. Most AI tools require a certain level of digital skills to be used effectively, but among several population groups, including older people, levels of digital literacy are especially low.[70] What is more, access to (expensive) technological tools or an adequate internet connection may be a problem for some groups of older patients. In their decision-making process on digitalisation, healthcare institutions often do not consider the lack of access to digital tools or low levels of digital literacy.[71]Many AI applications in themselves, such as AI mobile apps, are also not compatible with the needs of older patients, for example, due to their high-level digital infrastructure (e.g. complex features and lack of user instructions) and inaccessible design (e.g. small letters, or unexpected touch screen movement).[72] In the case of older patients with disabilities, additional accessibility issues may occur.[73] This form of digital exclusion creates barriers to accessing healthcare for – especially – older patients and can have a major impact on the right to access to healthcare.

Equally important is the degree of trust people place in the health professional or health system: non-trusting patients are more likely to avoid healthcare services or adhere to treatment plans. In general, empirical research shows that patients trust an AI system less than a human health professional, even if it performs at the level of a human health professional.[74] A recent survey conducted by the MIT AGELAB showed that consumers have ‘little to some willingness to trust a diagnosis and follow a treatment plan developed by AI, allow a medical professional to use AI for recording data and as a decision support tool, use in-home monitoring on the health issues of their own, and trust an AI prediction on potential health issues and life expectancy,’ especially for consumers in the higher age groups.[75] When AI becomes standard in healthcare, low levels of trust may cause access barriers for older patients.

4.2 BIASES, EQUALITY, AND HIGH-QUALITY HEALTHCARE

The right to access to healthcare also entails equal access to high-quality healthcare: health facilities, services, and goods should be culturally acceptable, scientifically appropriate, and of high quality.[76] The use of biased AI tools– the tendency of AI systems to make different decisions for certain groups on a structural basis – may result in unfair outcomes for a select group of individuals. AI systems often function less well for ‘data minority groups’ such as older people.[77] Biases can occur at any stage of the AI lifecycle: in the data stage, the modelling stage, and the application stage.[78]

In the data stage, when the data is collected and the system is trained based on this data, biases can – for example – arise because of outdated or incorrect data in the dataset, or because of the underrepresentation of certain population groups.[79] This is relatively common for older people since their data is often excluded from clinical trials due to comorbidity, and because they are less likely to use commercial technology that collects personal data.[80] This can cause incorrect decisions for older patients because the system is not familiar with certain age-specific symptoms.[81] At the modelling stage, where the purpose and rules of the AI are determined, biases may arise due to the selection of incorrect indicators or proxies, for example, if age is used as an indicator for preferred treatment,[82] or if the performance of an AI intended for elderly care is tested with a dataset consisting predominantly of young people’s data.[83] Finally, choices in the application stage can also create biases, for example if the AI is developed for use by clinical specialists, but in practice is used by GPs.[84] In conclusion, age-related biases in the various stages can impact the quality of healthcare and create an ‘AI cycle of health inequity’ for older people, eventually endangering equal access to healthcare.[85]

4.3 PRIVACY AND CONFIDENTIALITY

The development of AI leads to an increase in the collection, processing, exchange and sharing of sensitive health-related data, often outside the healthcare system, and for purposes not initially known to data subjects. AI systems both ‘consume’ personal data inputs and create outputs. In both phases, the rights to privacy and confidentiality of patients are at risk. In the data input phase, patients’ data can be used without consent (e.g. through web scraping), or patients can be (in)directly pressured to provide sensitive personal data. Generally, older people are particularly susceptible to this.[86] In addition, health data is increasingly ‘commodified’: personal data is reduced to an economic ‘good’ that can be bought and sold. Without adequate safeguards, highly personal information can end up in the wrong hands, for example, those of insurers, employers, and other commercial parties.[87] Further, the opaque nature of many AI applications also poses a challenge to patients’ access to, use of, and control over personal data.[88]

The output generated by AI can also create new challenges for privacy and confidentiality. To illustrate, AI tools used in elderly care, such as AI fall detection sensors, collect a lot of sensitive details about the lives of older patients for the purpose of data analysis. Doing this, AI systems generate new data about an individual person, for example a detailed profile of physical activity patterns, of which the patient is not necessarily aware.[89] Further, this type of ‘health surveillance’ is privacy-invasive and deprives patients of their freedom in the sense that they may modify their behaviour in response to ‘feeling observed’.[90] Subsequently, the data analytics can be used to make predictions about patients’ future behaviour. These predictions can then be used to make medical decisions, for example whether to lock the doors at night, which has direct consequences for older patient’s freedom.

4.4 INFORMATION, AUTONOMY, AND HUMAN DIGNITY

While AI applications can have positive effects on the autonomy of older patients (e.g. expanding the possibilities to live independently), they can also bring about risks to their right to self-determination. Older people often already experience reduced levels of autonomy concerning their lives and health, and AI systems may exacerbate this. One reason for this is the lack of transparency about the decision-making of many AI systems. This makes it difficult to explain outcomes or conclusions resulting from AI systems to patients.[91] As a result, this puts pressure on patients’ rights to information and the right to informed consent to medical treatment, especially for older patients.[92] This is exacerbated by the fact that decisions to use AI tools are usually not made by the patients themselves, but by health professionals or informal caretakers. Further, AI systems can also impact bodily integrity, for instance, if care robots are deployed for physical support such as washing. Finally, far-reaching intrusions into older people’s personal lives may eventually affect the protection of human dignity, for example, if extensive automation significantly reduces human contact for older patients. Unwarranted use of AI in elderly care for the objective of reducing workload puts us at risk of eventually dehumanising healthcare.[93] For this reason, it is important for health professionals to understand how to deploy AI in accordance with the core rights of patients.

5. A PROPOSAL FOR A PATIENTS’ RIGHTS IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR AI IN HEALTHCARE

5.1 THE EU REGULATORY PATCHWORK FOR AI IN HEALTHCARE

At this moment, there is no specific regulatory framework at the EU level that governs the use of AI applications in elderly care. Some AI products meet the definition of ‘medical device’ under the EU Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) and must comply with its quality and safety requirements to be marketed. However, this framework does not necessarily address the aforementioned challenges AI products for elderly care pose to patients’ rights. The MDR should primarily be seen as a safety and quality framework and mainly imposes rules on the developers of medical technology.[94] Indeed, the MDR does not apply to all medical AI products as it excludes products without an explicit medical purpose, such as products intended to improve ‘wellbeing’. Many home automation products fall into this category. Thus, for many AI products used in elderly care, only regular consumer law applies at the EU level.

Within the framework of EU consumer law, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the key legal instrument AI applications in elderly care must comply with, dictating rules for the processing of personal data. However, there has been much criticism about the compatibility of the GDPR with AI applications that collect, process, or store personal data. Because the GDPR was drafted before the emergence of advanced AI applications, it did not necessarily take into account the specificities of AI. For example, one of the core principles of the GDPR is that of data minimisation: limiting the amount of personal data collected, processed, or retained so that there is no unnecessary or excessive data collection. Data minimisation seems incompatible with the practice of AI development, where personal data is often collected and analysed on a large scale without full disclosure of the final purpose of the processing. On the other hand, the individual rights of the GDPR also apply when personal data are processed by an AI system. For instance, data subjects have the right to data erasure and to access personal data. It is important to note that, within the system of the GDPR, member states have a wide margin of appreciation when it comes to regulating health data: there are wide exceptions in some member states for its use for scientific or medical purposes.[95] This could limit some of the rights individual patients enjoy under the GDPR.

The EU is currently working on several legal instruments to specifically regulate AI products. These include the recently adopted EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), a new Product Liability Directive, and an AI Liability Directive. Under the AI Act, medical devices using AI (the AI system is a safety component of a medical device or is itself a medical device) are considered high-risk. This means they have to undergo a conformity assessment in order to enter the market and meet general safety and performance requirements. This includes high-quality data for training, validation and testing, documentation requirements, appropriate cybersecurity measures, and transparency obligations.[96] While the objective of these instruments is to reduce the risks deriving from AI, it is less suitable to address the specific challenges faced by patients, due to their horizontal application to all AI systems across all sectors. Moreover, coming from the European Commission, the proposals take a rather safety-based approach to streamline the internal market and do not directly create new rights for patients confronted with AI applications. Hence, while consumers can trust that AI products on the EU market are generally safe to use, the legislation does not guarantee a specific AI product is the best choice for a specific patient. The question is whether these initiatives will adequately mitigate the new risks posed by using AI in healthcare.[97]

At the same time, the EU has relatively limited power in the regulation and organisation of healthcare, thus healthcare is mainly regulated at the national level. member states could therefore provide for more specific rules in the realm of health, as long as this does not conflict with the AI Act’s ‘maximum harmonisation’ provisions – where member states cannot set more stringent standards for AI products.[98] In the Netherlands, for example, involuntary care for people with dementia or mental disability is governed by the Care and Compulsion (Psychogeriatric and Intellectually Disabled Persons) Act, which requires certain AI technologies to pass a review before they can be deployed in (nursing) home care. However, this law does not apply to all older people who encounter AI technology in a care setting. Moreover, not all EU member states have such legislation in place: in most member states, older patients are only protected by the general EU human rights framework.[99] In sum, the current legal landscape surrounding medical AI systems is a complicated patchwork of laws and policies that intersect and overlap at different levels.

5.2 THE NEED FOR A PRIA INSTRUMENT

In practice, the interplay of different legal instruments applicable to AI systems used in healthcare complicates the protection of patients’ rights of older patients. Healthcare institutions, health professionals, and informal carers are increasingly faced with the difficult question of whether an AI application is a good solution in a specific case. For this, the EU regulatory patchwork for AI in healthcare does not immediately provide solutions. Whilst the new EU framework on AI ensures that consumers can trust that AI products on the EU market meet minimum quality requirements, it does not necessarily regulate the use phase, while many of the risks for patients’ rights only then manifest. The legislation does not concern the manner in which the AI product is used in a specific setting, nor does it guarantee a specific AI product is the best choice for the treatment and care of a specific patient. It is also complicated to make an informed choice between different AI applications since there is little transparency on the safeguards of various products. Indeed, the rather abstract EU human rights framework – that applies generally throughout all sectors and settings – also does not provide concrete tools to assess the suitability of a specific AI system in the context of healthcare. In short, it is highly complex for health professionals and informal carers to assess how a concrete AI system can be deployed in a manner that respects the patients’ rights of persons concerned.

This creates the risk that the normative effect of the AI regulatory framework is limited in practice, and the deployment of AI in healthcare may unintentionally lead to human rights violations. Especially in the setting of elderly care – where patients are generally more vulnerable to human rights violations and often have limited autonomy – healthcare institutions should be able to guarantee the protection of patients’ rights in relation to the use of AI systems. An EU-wide assessment instrument for the use of AI applications in healthcare is currently absent. Such assessment instruments do exist for, for example, medical research with humans, and custodial measures in youth care. Healthcare institutions as well as health professionals, patients, and other consumers (e.g. informal carers) would benefit greatly from an assessment tool in their decision-making process.

Against this background, this paper proposes the outlines of a ‘patients’ rights impact assessment’ (PRIA) instrument for AI systems in healthcare. The proposal is grounded in two important assumptions: (1) the challenges posed by AI are so specific that they require a technology-specific assessment model[100] and (2) AI systems exhibit significantly different risks when deployed in the healthcare sector and therefore require a sectoral assessment model.[101]

The key objective of rights assessment instruments is to identify the intended and unintended consequences for the rights protection of the individual prior to making the final decision. In the business sector, ex-ante ‘impact assessments’ are already commonplace, such as carrying out the UN-demanded ‘human rights due diligence’ to identify the impact of business activities on human rights.[102] Another example is the ‘data protection impact assessment’ (DPIA) – a tool to analyse the privacy risks of a given personal data processing activity, which in some cases is mandatory under the GDPR.[103] The Artificial Intelligence Act prescribes a ‘fundamental rights impact assessment’ for certain categories of high-risk AI products.[104] The Dutch government also commits to a human rights assessment using the ‘Human Rights and Algorithms Impact Assessment tool’ when deploying algorithms for administrative decision-making.[105] A PRIA for AI in healthcare aligns with these developments.

The next Section describes the outlines of the PRIA for AI in healthcare. The proposed assessment model can be applied across the healthcare sector, but the next Section applies the PRIA to the context of AI in elderly care. The proposed model mainly serves to identify potential risks and contains limited normative standards. Eventually, within the boundaries of the legal framework, society should decide on the acceptability of certain risks posed by AI in healthcare, especially when AI is deployed to reallocate the scarce resources of health personnel in elderly care.

5.3 THE OUTLINES OF A PRIA INSTRUMENT: APPLICATION TO ELDERLY CARE

The objective of the proposed PRIA instrument is to provide practical guidance on the implementation and use of AI applications in healthcare in a manner that protects the health and rights of individuals. It can be applied in all EU member states. The instrument takes the form of a self-assessment questionnaire. For the design of the tool, inspiration was taken from the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,[106] the proportionality test performed by the ECtHR to balance competing interests and rights,[107] the DPIA in the GDPR,[108] and the Human Rights and Algorithms Impact Assessment of the Dutch government.[109] Following the human rights-based approach to health, the tool incorporates the current international human rights law framework. The tool is flexible and can be used in various settings within the healthcare domain.

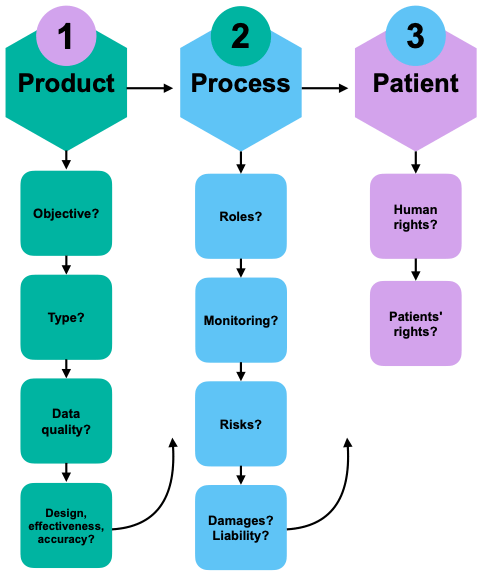

As seen in Figure 1 below, this instrument consists of three phases. Phase I relates to the purpose, functioning, and quality of a specific AI product, Phase II relates to the implementation of safeguards in practice, and Phase III relates to the rights of patients exposed to the specific AI application. The following section briefly explains the specific components of the PRIA instrument. To clarify its use in practice, it explains the tool through application to the context of an elderly care institute in an EU Member State.

Figure 1. Patients’ Rights Impact Assessment for Medical AI[110]

As seen in Table 1 below, the first phase of the PRIA focuses on the selection of a specific AI product to be used in the healthcare setting. Thus, the first question that comes up is who should carry out the PRIA. In the case of elderly care, it is not always the same actor who makes the final decision on the deployment of a specific AI system. The care for older persons is generally delivered in different places (at home; in nursing homes; in hospitals). When the patient is staying in a healthcare facility, it seems logical to place the responsibility for carrying out the PRIA on the management of the healthcare provider, e.g. a long-term care facility. They could appoint an ad-hoc committee within the healthcare institute to perform the assessment. In the Netherlands, the healthcare provider’s responsibility for the quality and safety of purchased products is explicitly embedded in the law. This task could also be assigned to the person who is the ‘controller’ within the meaning of the GDPR: the actor who determines for what purpose personal data are processed and how this is done.[111] The same principle could be applied to home care organisations using AI systems in older patients’ homes. If AI applications are prescribed as medical treatment by health professionals, it could be possible to make the tool part of a professional guideline, for example, issued by an association of health professionals that is concerned with self-regulation. An additional effect would be that the PRIA compels developers of medical AI tools to develop patient-centred tools and provide transparency about the specifications of the AI tool. Many questions in the PRIA, such as question c.1 on data sources, require clear information from the developer.

When AI products are chosen and purchased for home use by the patient or informal caretakers without the involvement of health professionals, it is more difficult to determine who should perform the PRIA. A first possibility would be to let the health insurer decide based on the PRIA whether to reimburse the costs of certain AI tools used for the home care of older patients. However, in most EU member states, this would require legislative amendments. In some member states, long-term care services are provided directly by the State. Thus, another possibility would be to assign the responsibility for performing the PRIA to the State. In the Netherlands, for example, technological tools to support daily living activities are reimbursed by the municipality under the Social Support Act. In that case, municipalities could carry out the PRIA to decide which AI tools to reimburse. For AI tools used for elderly care outside these frameworks, a labeling system could be an option. In that case, the developer of the medical AI application would have to perform the PRIA and publish the results in order to get a ‘PRIA-label’. This would allow individual consumers – e.g. patients or informal caretakers – to differentiate between more and less ‘patient-proof’ AI tools. Eventually, this would allow consumers to make a more informed decision on the selection of a specific AI system while at the same time encouraging developers to develop patient-centric products and improve transparency. In some cases, this labelling system comes on top of the already existing system of CE-marking for medical devices. Similar labeling systems have been proposed in the context of security labels for Internet of Things-devices,[112] and privacy labels for mobile apps.[113] A PRIA-labelling system would also command patient-centred development and transparency.

Table 1. Phase 1 – Product selection

| Topic | Questions | Explanation |

| (a) Objective of the AI application | a.1) What are the motivations for selecting this AI application? What is the intended effect of using the AI application? | An objective could be, for example, increasing staff productivity for labour savings, reducing patient loneliness, or increasing the accuracy of medical diagnoses. Multiple objectives may co-exist. It is important to identify all objectives, as a particular application may have positive effects on one, but at the same time pose risks to the achievement of another objective (e.g. health gains in terms of bone mass rates vs quality of life). |

| (b) Algorithm type specifications | b.1) Which AI application (type, developer) was selected and how does the AI application function? | Describe the product specifications and summarise the functioning of the AI application. Describe how the application is deployed in the healthcare process. |

| b.2) Is the algorithm of the AI application self-learning or non-self-learning? | Non-self-learning AI algorithms are programmed to perform specific tasks based on predefined rules and instructions. They do not change in response to new data and do not learn from experience (e.g. traditional expert systems and rule-based systems). Self-learning AI algorithms are designed to learn and improve from new data input. They adapt to new information and can improve their performance over time (e.g. neural networks and deep learning models). | |

| b.3) Why was this specific AI application selected to achieve the stated objective? What alternatives are available and why are they less appropriate or useful? | It is not always necessary to opt for a technological solution to achieve the same objective. Besides, there are intrusive and less intrusive AI applications. Some AI applications work better in the specific healthcare context (e.g. elderly care) than others. | |

| (c) Quality and reliability of data in the development phase | c.1) What data sources were used in the development of the AI application? Are these data sources reliable? | The output of the AI application depends on the training data used. This data must be of high quality (e.g. no poor-quality CT scans), accurate (e.g. not just self-reported symptoms), and representative of the context or population group in which the AI application is to be deployed (e.g. an AI application trained with data from predominantly students will not necessarily give the same results for patients of advanced age). |

| c.2) What biases may be embedded in the data sources used? | Biases can occur in all data sources used to develop, train, and evaluate AI applications. It is particularly important to look at the representation of different populations in the data sources, to identify, for example, cultural bias, ethnic bias, and age-related bias. | |

| c.3) Is the data representative of the specific care context? | To assess the quality and reliability of the data for a specific context, it is important that data sources that represent the target group (e.g. older patients) were used when developing the application, both in the training data and the evaluation data. | |

| c.4) Does the data comply with FAIR and FACT principles? | Note: The FAIR and FACT principles are principles for data management. It is common for organisations to be able to demonstrate that their dataset meets these requirements. These include principles of traceability, accessibility, interoperability, reusability, fairness, accuracy, confidentiality, and transparency. | |

| (d) Design, effectiveness and accuracy | d.1) Is the design of the application appropriate for use by older people? | There are often large differences in digital literacy between population groups. For example, it is useful to consider whether older people were involved in the development of the application. |

| d.2) Under what circumstances is the AI application deployed? | Note: The effectiveness of AI largely depends on the context for which the application has been tested and developed, and the context in which the application will be deployed. Specify the context in which the application will be deployed. In doing so, describe the target group for which the application will be used, the location where the application will be deployed, and for what period of time. | |

| d.3) How accurate is the AI application? | Explanatory note: Provide the accuracy score of the application. Describe the composition of the test dataset used to evaluate the quality and suitability of the model. Describe what criteria were used to evaluate the AI application. |

As seen in Table 2 below, the second phase focusses on the safeguards surrounding implementation of the AI system in a specific healthcare context. While the first phase of the PRIA is clearly guided by the quality and safety requirements as demanded by the AI Act, the second phase concerns the specific challenges of using AI tools in the context of healthcare. This phase is important because, in the case of AI tools, the use context is essential to the actual quality and safety of the tool. The product itself can be perfectly safe, but if there a no procedural safeguards in place, the health and rights of patients are still at risk. For example, the patient population of older patients differs significantly from patients in their twenties, because older patients did not grow up using technology and may react differently to the use of technology in medical treatment or health monitoring. The final part of the PRIA, part h about damages and liability, may compel healthcare institutes such as long-term care homes and home care organisations to design a specific complaint procedure for patients using AI. While some of the questions in the PRIA, such as e.3 and g.3, are more appropriate for healthcare institutions using the tool, these questions are equally important to informal caretakers using the tool, to raise privacy awareness.

Table 2. Phase 2 – Procedural safeguards

| Topic | Questions | Explanation |

| (e) Roles and responsibilities | e.1) Who are the users of the AI application? | Describe both users (e.g. nurses, informal caretakers) and end-users (e.g. patients in nursing homes, older patients using home care). |

| e.2) Who determines the purpose and means of the AI application? | ||

| e.3) Who are the controllers and processors under the GDPR? | See Article 4 of the GDPR. | |

| (f) Monitoring and evaluation | f.1) Who is responsible for monitoring? | |

| f.2) How does monitoring take place? | Describe the tools in place for evaluation and monitoring, and describe the criteria used. Indicate whether there is ‘a human in the loop’ in case of automated decisions. | |

| (g) Risk assessment and measures | g.1) What are the risks? | Identify the risks that could prevent the organisation from achieving its objectives. Also consider the DPIA under the GDPR. |

| g.2) What is the nature, characteristics, and level of risks? | ||

| g.3) What organisational and technical measures are taken to mitigate the risks? | Describe what agreements have been made about the management of the application, updates, and security of the AI application. | |

| (h) Damages and liability | h.1) What forms of damage can occur? | |

| h.2) Who is liable for what forms of damage? | ||

| h.3) What is the procedure when damage occurs? |

As seen in Table 3 below, the third phase focusses on the implications of the AI system on the rights of the specific patient. The first part of the rights assessment, part (i), focusses on human rights protection broadly, first identifying the potential impacts on various human rights, and then evaluating the balance of various rights and interests. This phase also requires a re-assessment of the objective of deploying a specific AI tool. The second part of this phase, part (j), concerns the patients’ rights dimension. The questions relate to the implementation of specific safeguards that indicate adequate protection of patients’ rights. While these aspects are already part of the regular obligations of health professionals towards patients, it is important to create awareness as to how the use of AI tools in healthcare can change the existing patient-health professional relationship. For informal caretakers who purchase AI tools for patients in home care situations, these questions can inspire a conversation with the patient about boundaries and preferences.

Table 3. Phase 3 – Assessing rights

| Topic | Questions | Explanation |

| (i) Human rights roadmap | i.1) What human rights are at stake in the deployment of the AI application? | Various human rights may be at stake in the deployment of the AI application, especially the right to privacy and data protection; the prohibition of discrimination; the right to health; the right to information; the right to autonomy and bodily integrity should be considered. |

| i.2) Is there a legal basis for restricting certain human rights? | Include an assessment of the applicable national legislation on healthcare and provisions on compulsory treatment. | |

| i.3) How badly is the human right affected? | It should be considered whether the core of the human right is affected. For the right to privacy, for example, core values are those of autonomy, human dignity, and mental and physical integrity. | |

| i.4) What are the objectives and is this particular AI application suitable to achieve these objectives? | The impact on the human right should be proportionate to the objective (e.g. protection of public health or improvement of workforce efficiency). | |

| i.5) Is this particular AI application necessary to achieve these goals? | Are other measures possible? Is it possible to take mitigating measures? Is a non-AI solution also possible? Are other – less restrictive – AI applications available? | |

| i.6) Is the deployment of this specific AI application proportionate to the stated objectives? | Does the specific objective justify a restriction? Is there a reasonable balance between the objective and the extent to which human rights are restricted? | |

| (j) Patients’ rights test | j.1) What safeguards are in place regarding transparency and explainability of the AI application? | Is it clear to the user (e.g. doctor, nurse, informal caretaker) how the AI application works? How is this explained to the patient? |

| j.2) What safeguards are in place regarding informed consent for the use of the AI application? | What does the process regarding informed consent look like? To what extent is the patient involved in decision-making about a specific AI application? Can the patient refuse the AI application and if so, what is the alternative? What is the procedure when the patient is legally incapacitated to make decisions? | |

| j.3) What safeguards are in place regarding the patient’s right to access personal data processed by the AI application? | ||

| j.4) What safeguards are in place regarding the patient’s right to erasure of personal data processed by the AI application? | ||

| j.5) What safeguards are in place regarding the right to complain if the patient is dissatisfied with the AI application? | ||

| j.6) Does the patient have other rights regarding the AI application? |

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The increasing use of AI in elderly care, driven by double ageing, the health workforce crisis, and increasing ‘technosolutionism’, necessitates thorough research into adequate implementation of AI systems for older patients. The lack of clear policy guidelines and regulations on the use of AI in healthcare makes it difficult for healthcare facilities, health professionals, and informal caretakers to make informed decisions on whether and how to use AI for a specific patient or patient group. This is an undesirable situation, as – especially in elderly care – AI systems can have significant implications for both the quality of healthcare and the protection of patients’ rights.

The proposed ‘patients’ rights impact assessment’ instrument aims to fill the regulatory gap by providing guidelines for the implementation and use of AI systems in healthcare. Various healthcare actors could use the tool to evaluate the implications of a specific AI application, depending on who is responsible for selecting and deploying specific forms of healthcare. In the case of elderly care, the main question is when the deployment of AI technology is justified in light of workforce shortages. In this challenging context, the PRIA tool can serve as a valuable compass for making the right decisions. It is recommended that associations of health professionals convene to further refine the tool and implement it in practice.

Indeed, an assessment tool of this nature cannot operate independently. It is essential to develop robust legal regulations that prioritise patient safety and the quality of AI technology implementation. Moreover, the question arises of whether the current human rights framework – on which the PRIA tool is based – adequately addresses the growing influence of AI in society. There may be a need for new human rights provisions specifically tailored to safeguard individuals from the risks posed by AI. For instance, should there be a ‘right to mental self-determination’ or a ‘right to meaningful human contact’? This necessitates a broad public debate. Nonetheless, given the rapid integration of smart health technology among vulnerable groups, regulatory measures cannot afford much delay, and the legislature will have to get ready to formalise a patients’ rights assessment tool for AI in healthcare.

[1] Eurostat (online data code: demo_pjanind), data extracted in February 2023. Updates are available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_population_developments, last accessed 22.05.2024.

[2] NIDI, ‘Policy choices in an ageing society’, (2022) 38 Demos Bulletin on Population and Society, available at https://nidi.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/demos-38-06-epc.pdf, last accessed 13.05.2024.

[3] WHO, ‘Health and Care Workforce in Europe: Time to Act’, 14.09.2022, available at https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289058339, last accessed 13.05.2024 .

[4] Social Affairs and Inclusion (European Commission) Directorate-General for Employment et al., ‘Challenges in Long-Term Care in Europe: A Study of National Policies’,2018, available at https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/84573, last accessed 13.05.2024.

[5] TNO, ‘Nursing Home Care Capacity Development Forecast’, 17.12.2019, available at https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/ronl-e7569fab-4e43-42aa-b29a-948ae34cd87d/pdf, last accessed 13.05.2024.

[6] See Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); Articles 2, 3 and 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) via the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR); Article 35 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (CFREU); Articles 11-13 of the European Social Charter (ESC).

[7] OHCHR and WHO, ‘The Right to Health’, Fact Sheet no. 31, 01.08.2008, available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-no-31-right-health, last accessed 13.05.2024.

[8] L. Taylor, ‘There Is an App for That: Technological Solutionism as COVID-19 Policy in the Global North’, (2021) The New Common, p. 209.

[9] See for example: Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport of the Netherlands, ‘Valuing AI for Health’, available at www.datavoorgezondheid.nl, last accessed 13.05.2024.

[10] E. Fosch Villaronga et al., ‘Implementing AI in Healthcare: An Ethical and Legal Analysis Based on Case Studies’, in D. Hallinan, R. Leenes and P. de Hert (eds.), Data Protection and Artificial Intelligence: Computers, Privacy, and Data Protection, Hart Publishing, Oxford 2021, pp. 187-216.

[11] G. Bardaro, A. Antonini and E. Motta, ‘Robots for Elderly Care in the Home: A Landscape Analysis and Co-Design Toolkit’, (2022) 14 Int. J. Soc. Robot., p. 657.

[12] J. Zhu et al., ‘Ethical Issues of Smart Home-Based Elderly Care: A Scoping Review’, (2022) 30(8) J. Nurs. Manag., pp. 3686-3699.

[13] G. Rubeis, ‘The Disruptive Power of Artificial Intelligence. Ethical Aspects of Gerontechnology in Elderly Care’, (2020) 91 Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr, p. 104186.

[14] A. Rosales and M. Fernández-Ardèvol, ‘Structural Ageism in Big Data Approaches’, (2019) 40(Special Issue 1) Nord. Rev., pp. 51-64.

[15] H. Van Kolfschooten, ‘EU Regulation of Artificial Intelligence: Challenges for Patients’ Rights’, (2022) 59(1) Common Mark. Law Rev., pp. 81-112.

[16] This chapter uses the term ‘older people’ in line with the recommendation of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, see United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), ‘General Comment No. 6: The Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of Older Persons’, contained in UN doc. E/1996/22, 08.12.1995.

[17] Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly, ‘Human rights of older persons and their comprehensive care’, Recommendation 2104 (2017), 30.05.2017.

[18] G. Rubeis (2020), ‘The Disruptive Power of Artificial Intelligence’, supra note 13.

[19] WHO, ‘Ageism in Artificial Intelligence for Health: WHO Policy Brief ‘, 09.02.2022, available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040793#, last accessed 21.05.2024.

[20] H. van Kolfschooten, ‘The AI Cycle of Health Inequity and Digital Ageism: Mitigating Biases Through the EU Regulatory Framework on Medical Devices’, (2023) 10(2) J. Law Biosci.

[21] A. Mantelero, ‘Regulating AI within the Human Rights Framework: A Roadmapping Methodology’, in P. Czech, L. Heschl, Lukas Karin et al. (eds.), European Yearbook on Human Rights 2020, Intersentia Ltd., Cambridge 2020, pp.477-502.

[22] B. Toebes et al., Health and Human Rights: Global and European Perspectives, Intersentia Ltd., Cambridge 2022.

[23] A. R. Niemeijer et al., ‘Ethical and Practical Concerns of Surveillance Technologies in Residential Care for People with Dementia or Intellectual Disabilities: An Overview of the Literature’, (2010) 22(7) Int. Psychogeriatr., pp. 1129-42.

[24] Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, ‘Domotics in long-term care – Inventory of techniques and risks’, 11.06.2013, available at http://www.rivm.nl, last accessed 13.05.2024.

[25] Ibid.

[26] J. Zhu et al., ‘Ethical Issues of Smart Home-Based Elderly Care’, supra note 12; N. Andrea Felber et al., ‘Mapping Ethical Issues in the Use of Smart Home Health Technologies to Care for Older Persons: A Systematic Review’ (2023) 24 BMC Medical Ethics.

[27] A. Poulsen, O. Burmeister and D. Tien, ‘A New Design Approach and Framework for Elderly Care Robots’, (2018) ACIS 2018 Proc. 75, available at https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2018/75, last accessed 21.05.2024; E. Fosch Villaronga, ‘Legal Frame of Non-Social Personal Care Robots’, in M. Husty, M. Hofbaur, (eds.), New Trends in Medical and Service Robots 229, Springer, Cham 2018, pp. 229-242.

[28] A. Mathew and N. Rana Mahanta, ‘Artificial Intelligence for Smart Interiors – Colours, Lighting and Domotics’, in 2020 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO), Noida, India 2020, pp. 1335-1338.

[29] A. Ho, ‘Are We Ready for Artificial Intelligence Health Monitoring in Elder Care?’, (2020) 20 BMC Geriatr., p. 358.

[30] Healthcare Vision, ‘AI in healthcare: successes, limitations and wishes’, 17.02.2021, available at www.zorgvisie.nl, last accessed 21.05.2024.

[31] M. Persson, D. Redmalm and C. Iversen, ‘Caregivers’ Use of Robots and their Effect on Work Environment – a Scoping Review’, (2022) 40(3) J. Technol. Hum. Serv., pp. 251-277.

[32] N. Gasteiger et al., ‘Friends from the Future: A Scoping Review of Research into Robots and Computer Agents to Combat Loneliness in Older People’, (2021) 16 Clin. Interv. Aging, pp. 941-971; J. Pirhonen et al., ‘Can Robots Tackle Late-Life Loneliness? Scanning of Future Opportunities and Challenges in Assisted Living Facilities’, (2020) 124(4)Futures.

[33] E. Fosch Villaronga (2018), ‘Legal Frame of Non-Social Personal Care Robots’, supra note 27.

[34] M. Cygańska, M. Kludacz-Alessandri and C. Pyke, ‘Healthcare Costs and Health Status: Insights from the SHARE Survey’, (2023) 20(2) International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, p. 1418.

[35] L. Westerbeek et al., ‘General Practitioners’ Needs and Wishes for Clinical Decision Support Systems: A Focus Group Study’, (2022) 168 International Journal of Medical Informatics.

[36] T. Ploug and S. Holm, ‘The Four Dimensions of Contestable AI Diagnostics – A Patient-Centric Approach to Explainable AI’, (2020) 107 Artif. Intell. Med.

[37] Z. Dlamini et al., ‘AI and Precision Oncology in Clinical Cancer Genomics: From Prevention to Targeted Cancer Therapies – an Outcomes Based Patient Care’, (2022) 31 Inform. Med. Unlocked.

[38] Some examples of key scholarship in the field of ‘health and human rights’ include: B. Toebes et al (2022), Health and Human Rights , supra note 22; .L. Gostin and B.M. Meier, Foundations of Global Health & Human Rights, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2020; J. V. McHale and T. K. Hervey, ‘Rights: Health Rights as Human Rights’, in V. McHale andT. K. Hervey (eds.), European Union Health Law: Themes and Implications, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2015, pp. 156-183; T. Murphy, Health and Human Rights, Hart Publishing, London 2013; M. A. Grodin et al. (eds), Health and Human Rights in a Changing World, Routledge, New York and London 2013; J. M. Mann et al. (eds), Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 1st edition, Routledge, Abingdon 1999.

[39] S. Gruskin, E. J Mills and D. Tarantola, ‘History, Principles, and Practice of Health and Human Rights’, (2007) 370 The Lancet, pp. 449-455.

[40] S. Gruskin, ‘What Are Health and Human Rights?’, (2004) 363 The Lancet, p. 329; A. de Ruijter, EU Health Law & Policy: The Expansion of EU Power in Public Health and Health Care, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2019.

[41] J. Rothmar Hermann and B. Toebes, ‘The European Union and Health and Human Rights’, (2011) 4 European Human Rights Law Review, pp. 419-436.

[42] See Article 12 ICESCR; Article 25 UDHR; Articles 2, 3 and 8 of the ECHR via the ECtHR; Article 35 of the CFREU; Articles 11-13 of the ESC.

[43] L. Forman et al., ‘What Do Core Obligations under the Right to Health Bring to Universal Health Coverage?’, (2016) 18(2) Health and Human Rights, pp. 23-24.

[44] B. Toebes, ‘The Right to Health’, in A. Eide, C. Krause and A. Rosas (eds.), Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2nd edition, Brill-Nijhoff, Leiden 2001, pp. 169-190.

[45] Preamble of the Constitution of the World Health Organization; B. M. Meier, ‘Human Rights in the World Health Organization’, (2017) 19(1) Health and Human Rights, pp. 293-298.

[46] B. Toebes et al. (2022), supra note 22; L. London, ‘What is a Human-Rights Based Approach to Health and Does It Matter?’, (2008) 10(1) Health and Human Rights, pp. 65-80.

[47] S. Porsdam Mann, V. J. Bradley and B. J. Sahakian, ‘Human Rights-Based Approaches to Mental Health’, (2016) 18(1) Health and Human Rights, pp. 263-276.

[48] J. Dute, ‘Communicable Diseases and Human Rights’, (2004) 11(1) European Journal of Health Law, pp. 45-53.

[49] T. Murphy, New Technologies and Human Rights, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2009.

[50] A. E. Yamin, When Misfortune Becomes Injustice: Evolving Human Rights Struggles for Health and Social Equality, 2nd edition, Stanford University Press, Stanford 2023.

[51] A. E. Yamin (2023), When Misfortune Becomes Injustice, supra note 50, p. 8.

[52] Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Patients’ rights’, (2008) OJ C 10/67.

[53] J. Boldt, ‘The Concept of Vulnerability in Medical Ethics and Philosophy’, (2019) 14(6) Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 6.

[54] B. Toebes et al. (2022), supra note 22, p. 10.

[55] W. Palm et al., ‘Patients’ Rights: From Recognition to Implementation’, in E. Nolte, S. Merkur and A. Anell, Achieving Person-Centred Health Systems: Evidence, Strategies and Challenges, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2020, pp. 347-387.

[56] A. de Ruijter (2019), EU Health Law & Policy, supra note 40.

[57] Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Oviedo, 4 April 1997).

[58] H.S. Aasen and M. Hartlev, ‘Human Rights Principles and Patient Rights’, in B. Toebes et al., Health and Human Rights: Global and European Perspectives, 2nd edition, Intersentia Ltd., Cambridge 2022, pp. 53-87.

[59] ECtHR, Trocellier v. France, no. 75725/01, 05.10.2006, para. 4.

[60] H. Nys, ‘Comparative Health Law and the Harmonization of Patients’ Rights in Europe’, (2001) 8(4) European Journal of Health Law, pp. 319-331.

[61] H.S. Aasen and M. Hartlev (2022), ‘Human Rights Principles and Patient Rights’, supra note 58, p. 65–66.

[62] WHO, ‘Global report on ageism’, available at www.who.int, last accessed 21.05.2024.

[63] Ibid.

[64] N. Hardwick et al., ‘Human Rights and Systemic Wrongs: National Preventive Mechanisms and the Monitoring of Care Homes for Older People’, (2022)14(1) J. Hum. Rights Pract., pp. 243-266.

[65] E.-Shien Chang and B. R. Levy, ‘High Prevalence of Elder Abuse During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk and Resilience Factors’, (2021) 29(11) Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry, pp. 1152-1159; Y. Yon et al., ‘The Prevalence of Elder Abuse in Institutional Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, (2019) 29(1) Eur. J. Public Health, pp. 58-67.

[66] ocial Affairs and Inclusion (European Commission) Directorate-General for Employment et al., ‘Challenges in Long-Term Care in Europe’, supra note 4.

[67] T. Leclerc et al., ‘Prioritisation of ICU Treatments for Critically Ill Patients in a COVID-19 Pandemic with Scarce Resources’, (2020) 39(3) Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med., pp. 333-339.

[68] M. N. I. Kuylen et al., ‘Should Age Matter in COVID-19 Triage? A Deliberative Study’, (2021) 47(5) J. Med. Ethics 291, pp. 291-295.

[69] WHO, ‘Ageism in artificial intelligence for health’, available at www.who.int, last accessed 21.05.2024.

[70] Ibid.

[71] F. Mubarak and R. Suomi, ‘Elderly Forgotten? Digital Exclusion in the Information Age and the Rising Grey Digital Divide’, (2021) 47(5) Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ., pp. 291-295.

[72] M. Gomez-Hernandez et al., ‘Design Guidelines of Mobile Apps for Older Adults: Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis’, (2023) 11 JMIR MHealth UHealth.

[73] B. Mikołajczyk, ‘Universal Human Rights Instruments and Digital Literacy of Older Persons’, (2023) 27(3) Int. J. Hum. Rights 403, pp. 403-424.

[74] R. Yokoi et al., ‘Artificial Intelligence Is Trusted Less than a Doctor in Medical Treatment Decisions: Influence of Perceived Care and Value Similarity’, (2021) 37(10) Int. J. Human–Computer Interact, pp. 981-990.

[75] Mit Agelab, ‘AI and longevity: Consumer and expert attitudes toward the adoption and use of artificial intelligence’, p. 33, available at https://agelab.mit.edu/static/uploads/mit-agelab-ai-longevity_wp-04-21-1357_ada.pdf, last accessed 21.05.2024; J. Stypińska and A. Franke, ‘AI Revolution in Healthcare and Medicine and the (Re-)Emergence of Inequalities and Disadvantages for Ageing Population’, (2023) 7 Front. Sociol.

[76] CESCR, ‘General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Article 12)’, 11.08.2000, contained in UN doc. E/C.12/2000/4.

[77] K. Wang, L. Zhou and D. Zhang, ‘Biometrics-Based Mobile User Authentication for the Elderly: Accessibility, Performance, and Method Design’, (2023) 40(9) Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 1, pp. 2153-2167.

[78] H. van Kolfschooten (2023), ‘The AI Cycle of Health Inequity and Digital Ageism’, supra note 20.

[79] D. Leslie et al., ‘Does “AI” Stand for Augmenting Inequality in the Era of Covid-19 Healthcare?’, (2021) 372(304) BMJ..

[80] S. Florisson et al., ‘Are Older Adults Insufficiently Included in Clinical Trials? An Umbrella Review’, (2021) 128(2) Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol, pp. 213-223.

[81] S. K. Inouye, ‘Creating an Anti-Ageist Healthcare System to Improve Care for Our Current and Future Selves’, (2021) 1 Nat. Aging, pp. 150-152.

[82] D. Neal et al., ‘Is There Evidence of Age Bias in Breast Cancer Health Care Professionals’ Treatment of Older Patients?’, (2022) 48(12) Eur. J. Surg. Oncol., pp. 2401-2407.

[83] R. Banzi et al., ‘Older Patients Are Still Under-Represented in Clinical Trials of Alzheimer’s Disease’, (2016) 8(32) Alzheimers Res. Ther.

[84] W. Nicholson II Price, ‘Medical AI and Contextual Bias’, (2019) 33(1) Harv. J. Law Technol. Harv. JOLT, pp. 65-116.

[85] H. van Kolfschooten (2023), ‘The AI Cycle of Health Inequity and Digital Ageism’, supra note 20.

[86] G. Malgieri and J. Niklas, ‘Vulnerable Data Subjects’, (2020) 37 Comput. Law Secur., Rev. 105415.

[87] L. Kumar Ramasamy et al., ‘Secure Smart Wearable Computing through Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems for Health Monitoring’, (2022) 22(3) Sensors, p. 1076.

[88] A. McNeill et al., ‘Functional Privacy Concerns of Older Adults about Pervasive Health-Monitoring Systems’, (2017) 96 Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, pp. 96-102.

[89] D. J. Solove, ‘Artificial Intelligence and Privacy’, 29.02.2024, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4713111, last accessed 21.05.2024.

[90] L. F. Carver and D. Mackinnon, ‘Health Applications of Gerontechnology, Privacy, and Surveillance: A Scoping Review’, (2020) 18(2) Surveill. Soc., p. 216.

[91] I. Glenn Cohen, ‘Informed Consent and Medical Artificial Intelligence: What to Tell the Patient?’, (2020) 108 Georgetown Law J., pp. 1425-1469.

[92] T. Seedsman, ‘Aging, Informed Consent and Autonomy: Ethical Issues and Challenges Surrounding Research and Long-Term Care’, (2019) 3(2) OBM Geriatrics, p. 1.

[93] K. Pfeifer-Chomiczewska, ‘Intelligent Service Robots for Elderly or Disabled People and Human Dignity: Legal Point of View’, (2023) 38 AI Soc., pp. 789-800); L. Zardiashvili and E. Fosch Villaronga, ‘AI in Healthcare through the Lens of Human Dignity’, in M.F. Bollon and A.B. Suman, Legal, Social and Ethical Perspectives on Health & Technology, Presses Universitaires Savoie, Mont Blanc 2020, pp. 45-64.

[94] H. van Kolfschooten (2023), ‘The AI Cycle of Health Inequity and Digital Ageism’, supra note 20.

[95] F. Molnár-Gábor et al., ‘Harmonization after the GDPR? Divergences in the Rules for Genetic and Health Data Sharing in Four Member States and Ways to Overcome Them by EU Measures: Insights from Germany, Greece, Latvia and Sweden’, (2022) 84 Semin. Cancer Biol., pp. 271-283.

[96] See articles 9-17 of the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain union legislative acts, 2021/0106 (COD) (full final draft of February 2024).